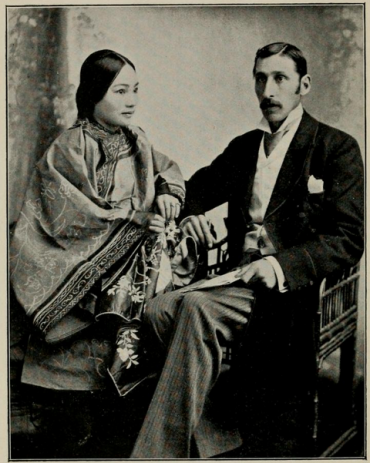

Charles Halcombe and Liang Ahghan, c.1896

An 1853 editorial in The Times had great fun with the idea that one day soon travel to China would be so easy and ordinary, so vulgar indeed, that ladies’ maids with carpet bags would be traipsing along the Great Wall. Vulgarity was signalled by the leader writer by a reference to the otherwise inoffensive north Kent coastal town of Herne Bay, which had been transformed rapidly by the arrival of the railway and some shrewd developments, not least a pier, into a very popular seaside resort. It seems somehow appropriate then to find Charles J. H. Halcombe, late Chinese Maritime Customs, living there in March 1901 with his wife Liang Ah Ghan.

Halcombe’s books might strike a faint chord: Called out; or, The Chung Wang’s daughter, an Anglo-Chinese romance (1894); The Mystic Flowery Land: A Personal Memoir (1896) — from which this photograph comes — and Children of far Cathay : a social and political novel (1906). The first and last are romances of anti-Manchu revolution — in the latter Sun Yat-sen makes an early fictional appearance — and ‘Anglo-Chinese romance’. Halcombe had joined the Customs Service as a Watcher in November 1887 and resigned when stationed at Kiungchow (Qiongzhou) in March 1893. He was by then a Second Class Tidewaiter, and he had a novel in his pocket. The grandson of a barrister and Member of Parliament, and son of a civil servant, Halcombe would evidently prove more comfortable with the occupation of author, with which he described himself in the 1901 census, and traveller, that local newspaper profiles accorded him in Kent. Twice ship-wrecked as a teenage sailor — in December 1881 off the French coast, and in January 1883 off Cape Horn — he also spent some time in South Africa before sailing into Shanghai in May 1887 aged 22. He tells us that he initially secured a post on the North China Daily News, but swapped that for the lowly position of Customs Service Tidewaiter, which is an unusual trajectory. Most men would aim to move the other way.

The Mystic Flowery Land is not a forgotten classic: its prose is clunky, its tone sentimental, and its claims to authority underwhelming. Several of its chapters began as articles in the monthlies, and it was perhaps to further his journalistic career that Holcombe arrived back in England with his wife in October 1894. He span a tale in one of its chapters about Liang Ahghan, the Cantonese woman he had met in Yantai (Chefoo) in north China when stationed there in 1888-89, and claimed that she had saved his life from rebels. This seems rather unlikely, but she moved with him from posting to posting, and they married sometime in late 1892 or early 1893 when he was based at Kiungchow, before he resigned and moved to Hong Kong.

Halcombe made an attempt at his literary career, but it proved hard-going. He had not received much schooling, and for the reviewers this showed. The author was ‘a clever man’, remarked The Westminster Review in 1899 in a notice of his novel about reincarnation and ancient Rome, The Romance of a Former Life, ‘but we doubt whether he has yet mastered the art of fiction’. “One reads on from page to page wondering what extraordinary mistake the good man will make next’, wrote Country Life‘s reviewer, patronisingly, of ‘the flood of childish and pretentious errors’ to be found in its pages. In 1905 Halcombe placed a letter in the Daily Mail offering a reward for the return of his journals which recorded the shipping disasters that he had survived, and which had been lost when his parents moved home. He was planning a work on his early travels, but his seems to have been a forlorn request, and neither the diaries nor the book seem ever to have appeared. His writing trailed off after 1906.. Halcombe died in May 1931 in Dover, noted still as an author and traveller, but also as a former local councillor, and civil servant, altogether a more secure occupation than novelist, or, particularly in his case, sailor.

It is Nina — Liang Ahghan — I think of, however. There are few traces of her outside her husband’s various references in his writings: in June 1900 she was baptised in a Herne Bay church; she appears in the 1901 and 1911 census; and she is nearly always mentioned in local press accounts of Halcombe’s work. There were 1,825 people born in China recorded in the 1911 census of England & Wales, although many of those were, unlike Liang Ahghan, not Chinese, but the offspring of missionary, commercial or Customs service families — as were Herne Bay’s two other China born residents. (The couple themselves had no children). What were the dynamics of the household caught in the 1911 census: the author manqué – pompously careful to have his status as District Councillor recorded on the form — his widowed 78 year old mother, the 18 year-old Kent woman who was the household domestic, and Liang Ahghan. A more agile novelist then Halcombe — a man whose books mostly fictionalised and mythologised his own life, and which repeatedly picked over his culturally brittle relationship — could make something of that, perhaps a comedy of manners and nations set against the backdrop of Herne Bay’s pier. Liang survived her husband by the best part of two decades and seems to have died in late 1949, in Folkestone. I wonder about her later life, and of what she made of these towns of coastal Kent after Yantai, Canton, and Hong Kong. We are left only with her husband’s mythologisation of her life, and of her father — who forms the subject of one essay in The Mystic Flowery Land (available in a 2009 Chinese translation, for some reason) — and this rather touching photograph of an Anglo-Chinese marriage.