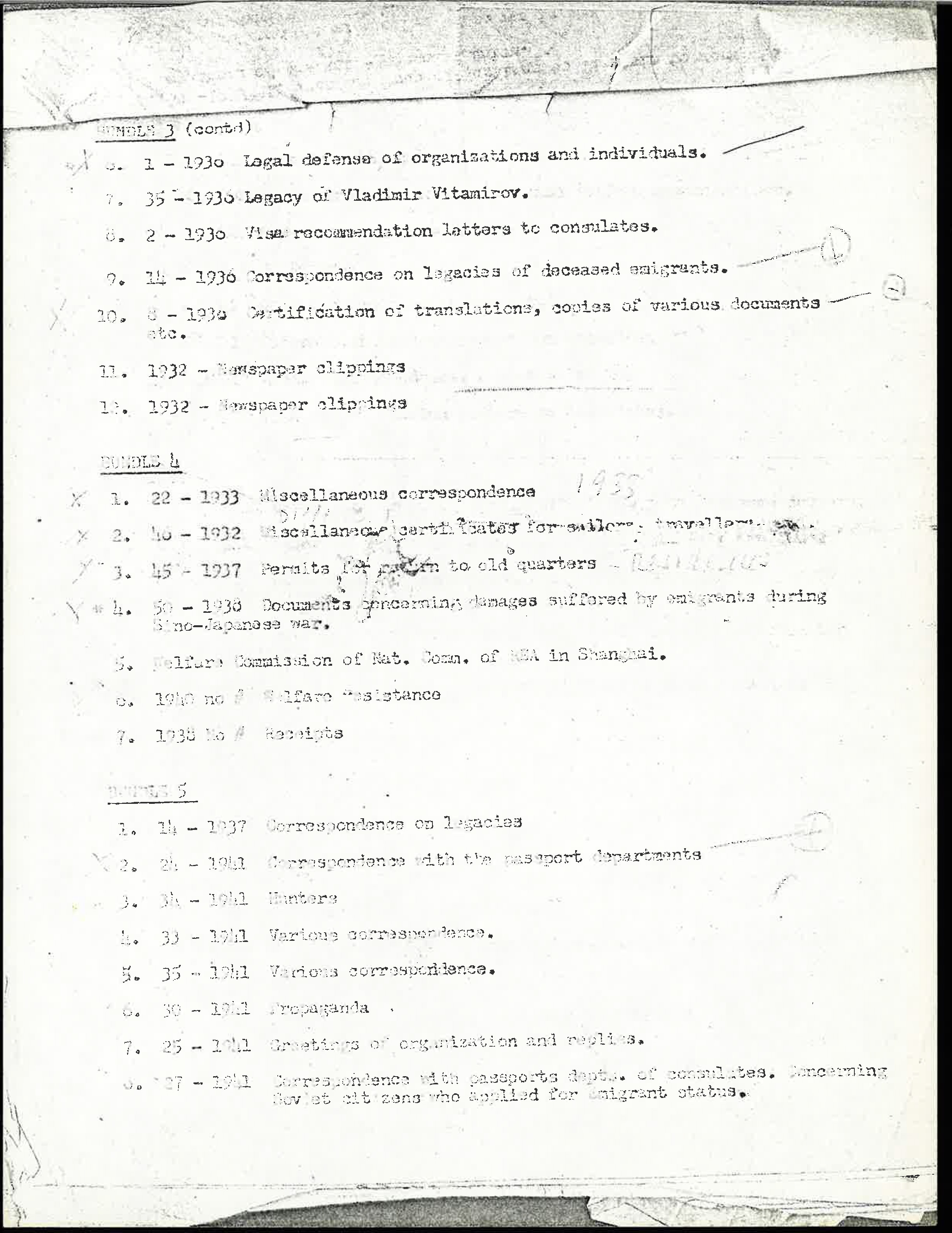

As a historian, I dwell in the past in more ways than one. Unlike some of my peers, I remain curious about stories once told, and as new resources come online, or I visit new archives, I will in quiet moments submit old names of those whose lives I have looked into to see if anything interesting comes to light. Sometimes it does.

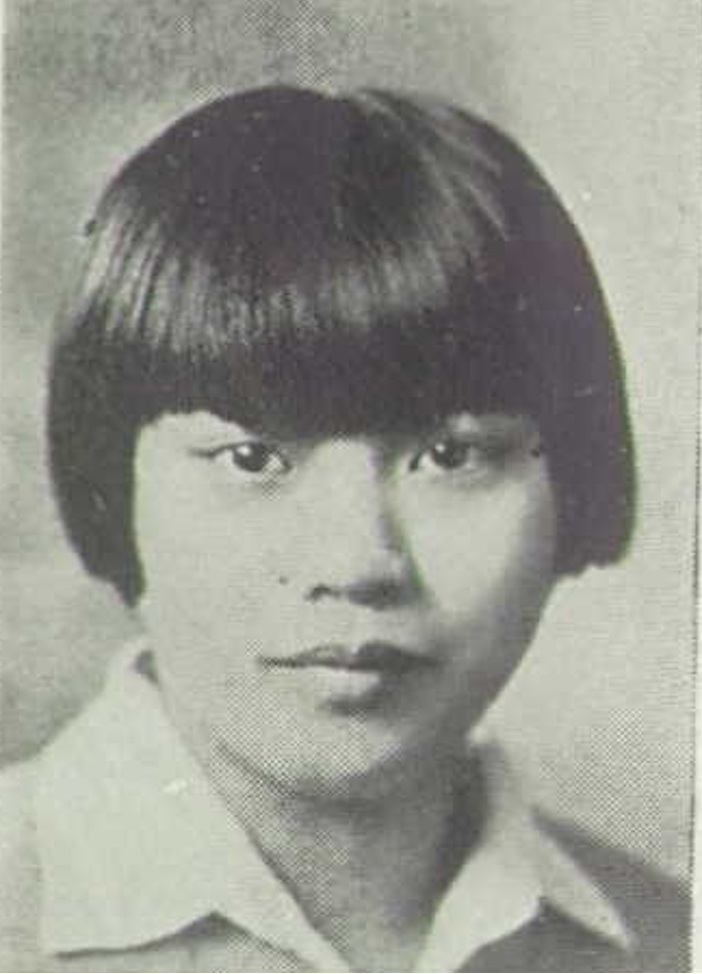

John Thorburn, 1931

One early story I pursued and wrote up concerned the disappearance and death in 1931 of a nineteen-year-old British boy, John Thorburn (left). This young fantasist stole away from his home in Shanghai and set off for adventure and to ‘make good’. Unhappily he carried two revolvers and by the end of the day had used them, to lethal effect, fatally wounding two Chinese gendarmes who challenged him as he walked along a railway line in the dark. Within twenty-four hours he had been apprehended by Chinese military police, from whose custody he never emerged. Thorburn was killed and his body secretly disposed of. Details of his fate were not uncovered for over five months. Meanwhile, his disappearance galvanized British residents in Shanghai both to demonstrate their fears for their safety in the face of Chinese moves to reform legal protections that should have led to his being promptly handed over the British after his arrest, and of course to lobby for his return, or for retribution if he were dead.

Thirty years ago this month, I gave a seminar paper on the affair for the first time, luridly titling it ‘Tortured, mutilated or dead’, then submitted it to the journal Modern Asian Studies, where it appeared after a long delay as ‘Death of a Young Shanghailander: The Thorburn Case and the Defence of the British Treaty Ports in China in 1941’. You can read the published version here, and if you do not have access to that, you can read the mss text here. I found my sources in the Public Record Office at Kew, the US National Archives in Washington DC, the Shanghai Library and the National Library of China in Beijing. Aside from the essential mystery of what John Thorburn was actually up to, which remained unclear, I felt I had sources that covered all the angles that interested me and supported the argument that I was making.

There was one exception, the identity of a ‘Mrs W. P. Roberts’, a ‘young married woman’, in whose company Thorburn spent most of the evening before his departure, and who was the bearer of his final farewell letter to his father. British diplomats decided to keep her out of the limelight, for the sake of her reputation, and I was unable to identify her. This was not important, but it did rankle. I ransacked newspapers and directories for ‘W. P. Roberts’, assuming that the convention of identifying a married woman by her husband’s initials held true in this case. Aside from tying up loose ends, this was one of the points that audiences asked me about when I gave talks on it. The appeal of a having a mystery shared with you, I learned, partly lies in trying to help solve it. It was a talk that engaged its listeners, who provided helpful reflections and challenges. Some I dealt with as I revised the paper. But I could not track Mrs W. P. Roberts down.

John Thorburn (top row, far left) and his father (bottom row, far right), Shnghai Volunteer Company, Light Horse, 1931

My colleague Tom Larkin has helped me solve the mystery and in a way that unexpectedly threads our work together. Tom is just about to leave the University of Bristol, where he has worked with me on his doctorate and as a research fellow, since 2017 with what is now the Hong Kong History Centre. He is moving to take up an Assistant Professorship in the History of the United States at the University of Prince Edward Island. He will be there when his fine book appears in print next year with Columbia University Press. The China Firm: American Elites and the Making of British Colonial Society is a wonderful study of the world of the men and women associated with the American trading company Augustine Heard & Company, in nineteenth-century Hong Kong. That work intersects with mine in ways we both know, for Heards helped John Samuel Swire establish his business in China and Japan in the late 1860s, an episode I discuss in my history of the British firm, China Bound: John Swire & Sons and its World (which has just appeared in translation in Taiwan).

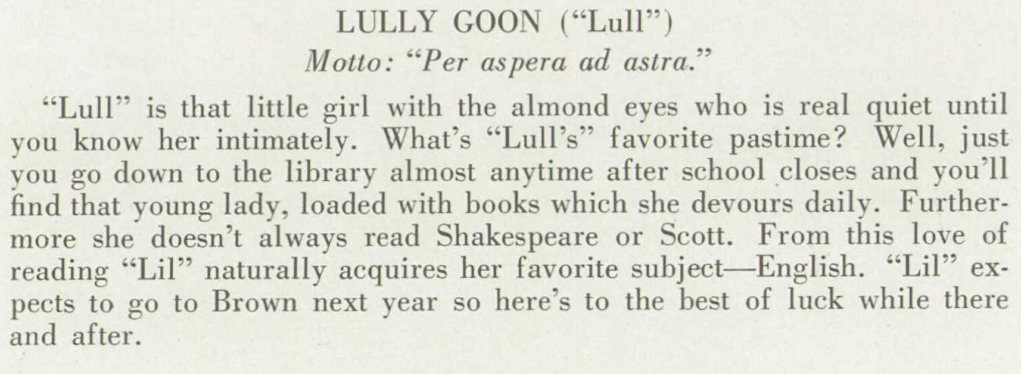

Tom came to Bristol fresh from an MA at the University of York in Toronto. His dissertation there explored representations of the shooting in Shanghai of an Englishman called Harry Smith in 1906 by a Macanese, Peter Sidney Hyndman, who had been born in Hong Kong. Smith had invited Hyndman’s fiancé Winifred Dorothy Rose to tea. Hyndman, who had asked her not to go, burst in to find her ‘in a state of undress’. He had a revolver with him, shot Smith dead, and accidentally wounded Winifred. Tom used this episode to present a rich picture of the fears of white society in treaty port society about the threats to its position posed by such ‘undesirables’ (and that discourse zeroed in on the alleged behaviour and mores of Winifred Rose, barely eighteen, already widowed, and of mixed Irish and Asian parentage). Hyndman was spared the gallows. In fact, he served only an eighteen-month sentence for manslaughter and lived on and worked in Shanghai until his death in 1936, and yes, dear reader, Winifred married him. You can read the article Tom drew out of his dissertation either here as published, or here, in manuscript.

There are obvious themes that both our papers share, and we have both benefited from other people’s misery. Violent death generates paperwork and newsprint, and freezes people at a particular moment in time. It seems callous to say so, but it is a gift for the historian. The disappearance of John Thorburn and the killing of Harry Smith allowed each of us to look in different ways at Shanghai’s foreign world at points a quarter of a century apart, and these incidents provided us with a rich set of materials to use as we did so. The essays are different in many ways, not least in terms of the wider political environment in which they are set – the last years of the Qing on the one hand, and the early years of the Guomindang republic on the other, and international society before and after the First World War. But the world of colonial power, even if under threat as it was in 1931, encompasses both of our articles.

So does the Hyndman family. I now know that Mrs W. P. Roberts was baptized Winifred Dorothy Hyndman. She was born in April 1911, and would be the only child of the marriage of Peter Sidney Hyndman and Winifred Dorothy Rose. I had been misled for years — for thirty years — by a typo, and by a Shanghai policeman’s inconsistency in referring to Thorburn’s ‘young married’ friend in this way. Winnie Hyndman was barely a month and a half older than John. She had been married just as she turned 15 to a British employee of a tobacco company, John Chamberlain Roberts, and gave birth to their first child a year later. John Roberts was in Britain when Thorburn went missing, and Winnie was living with her parents in Shanghai. Perhaps it was also cautiousness about stirring memories of the lively early years of that couple’s relationship, as well as the potentially compromising presence of Winnie in John Thorburn’s company in the last hours he spent in Shanghai that led the police and diplomats to be reticent. British officials presented the missing youth as an upright, decent young man, who had been naïve, foolish, and unlucky. They did not want anything to complicate that picture.

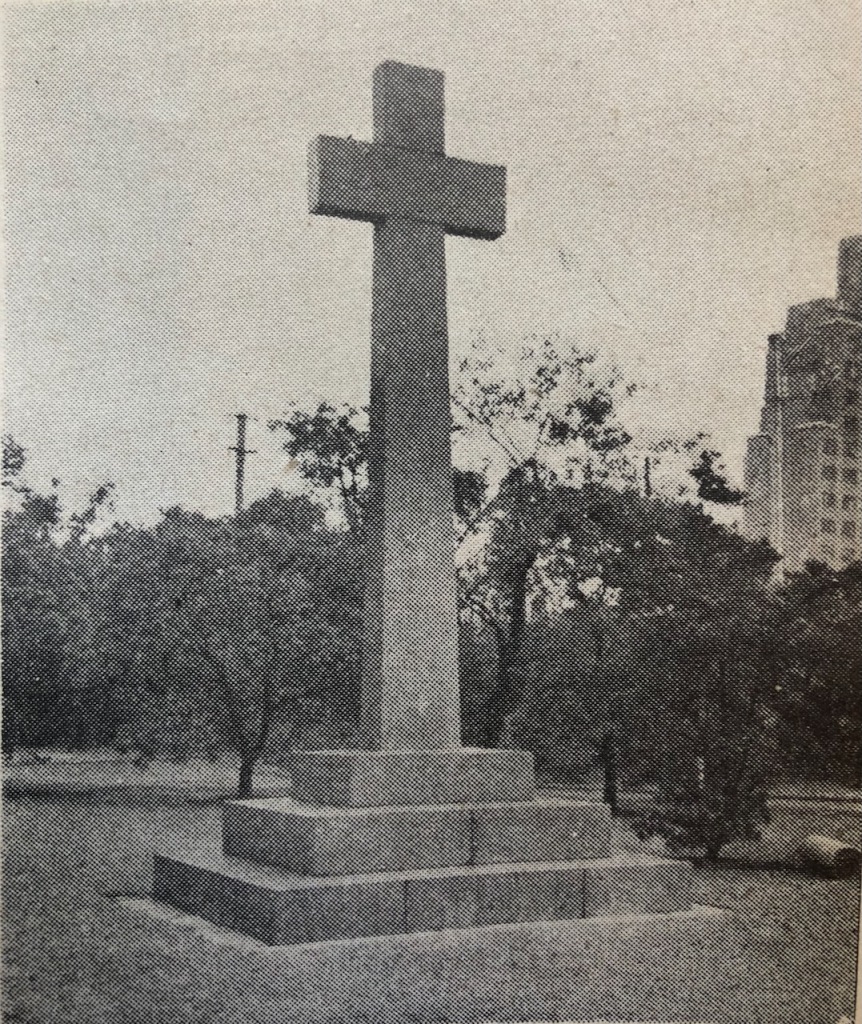

Bride and groom: Winnie and her husband, J.C. Roberts. Her parents stand on either side of them: China Press, 23 May 1926, p. D1

Our two research projects, initially undertaken a quarter century apart, can be linked together though the figure of Winifred Dorothy Hyndman, who died of tuberculosis in a hospital in Qingdao in 1937, and her parents. She was buried in the city’s International Cemetery, which is now a park. I doubt either article would have needed any changing if this connection had come to light earlier. It might have occasioned a comment, though. I had filled in other gaps since I completed the project. I found that Thorburn’s father lived in Shanghai until he died in 1957, long after the vast majority of Britons had left, and that after his death his Russian partner brought his ashes to Hong Kong where a remembrance service was held. I was contacted by relatives of some of those involved, who shared photographs and observations. I found another image myself, such as the one above of Thorburn in Shanghai Volunteer Corps uniform. Much remains unknown and unfathomable about John Thorburn’s adventure. But at least, finally, thirty years on, I have identified Mrs W. P. Roberts, Winifred Dorothy Roberts – Winnie Hyndman – and her history.

Thank you, Tom, and bon voyage.