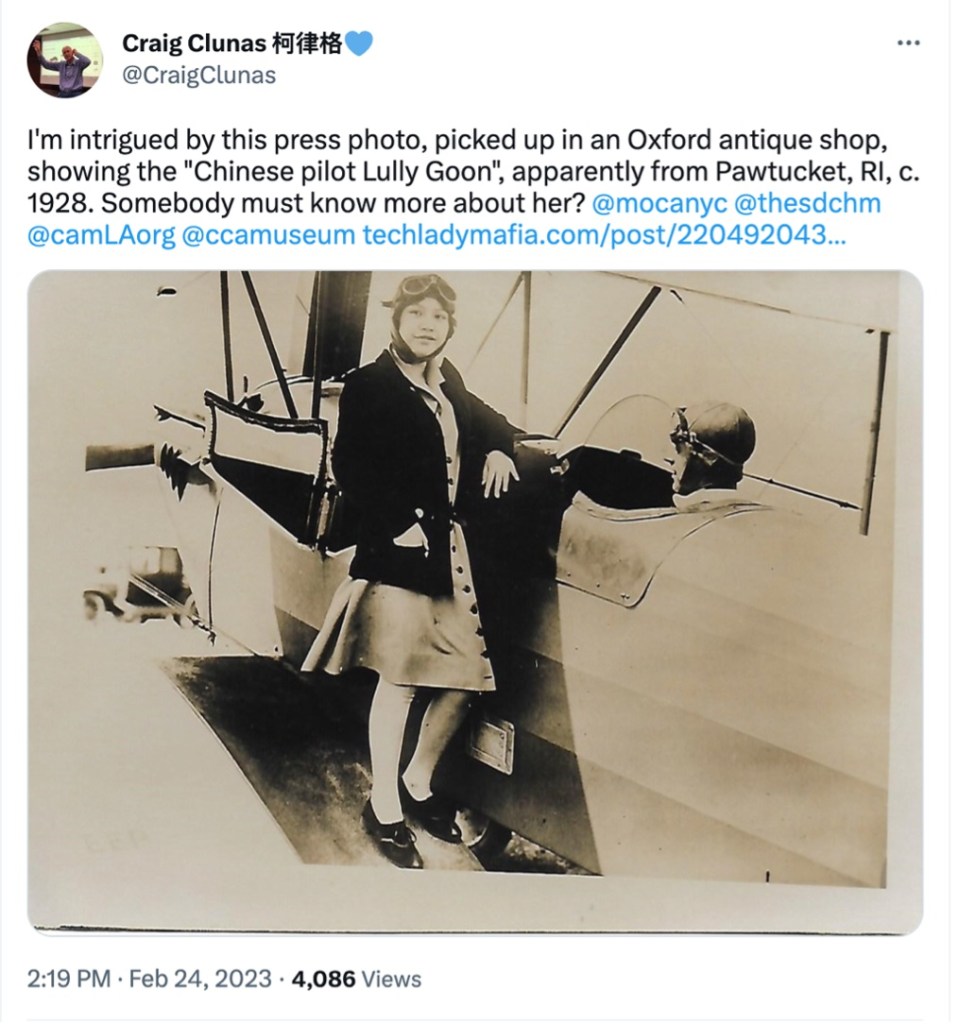

The tweet included an eye-catching image, and a mystery.

I have since found this photograph of Lully Goon in over 50 north American and European newspapers, but there will have been more. She was ‘Un succès féminste en Chine nationaliste’ for Le Petit Journal, her tale growing grander as it echoed further and further: she was ‘a flying instructor to Chinese Nationalist Air Recruits’, for the Auckland Star, ‘she is preparing for an air trip from New York to London’. Her story was carried in as many newspaprs again without the picture, or with a variant of it. Craig Clunas’s print was issued by a German press agency, and had a pencilled Spanish translation of the caption on the reverse: Lully certainly travelled. While there were a few versions of a moderately sized profile, most ran the photograph with a very simple explanatory caption. The news interest lay in the novelty of a young Chinese woman with ambitions to become a pilot and then to train pilots in China. But after her photograph flew around the world in 1928, little more was ever heard of, or could be found out about, Lully Goon.

The first Chinese American woman pilot is generally said to be Guangdong-born Katherine Sui Fun Cheung, who received her private pilot’s licence in March 1932 in Oakland, California, and later flew commercially. Hazel Ying Lee, born in Oregon, gained hers in October 1932, and later flew for the US Air Force. The FAA introduced licencing in 1927, so perhaps this photograph shows that Lully got her wings first. Certainly, it’s assumed that it records a pilot, or at least a pilot in the making.

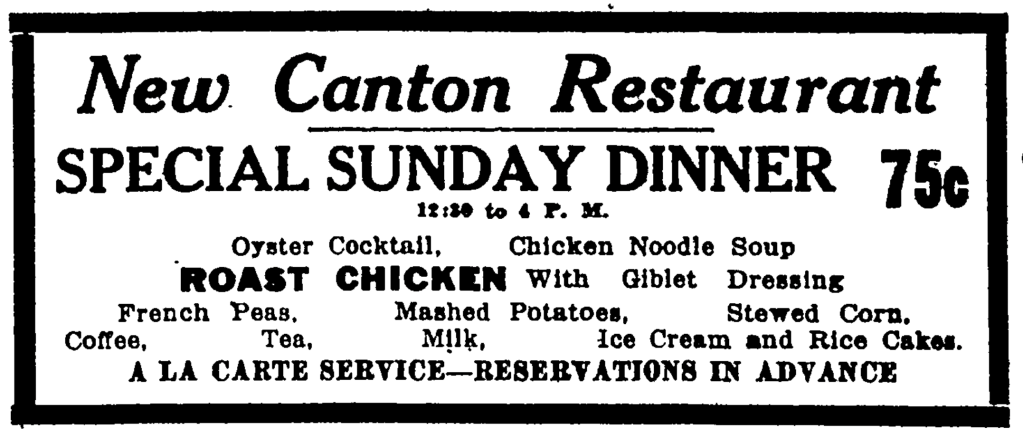

It doesn’t, but it is an interesting story nonetheless and surely, emperors excepted, there can have been few living teenagers of Chinese descent whose image had ever before been so widely circulated internationally as Lully Veda Goon’s was in the summer of 1928. Recorded at her birth in Boston in 1910 as Lillian Goon, but afterwards always referred to as Lully, this aviatrix was the eldest of the five children of Tacoma, Washington born Henry Lun Goon and Moy Shee. The Goons lived in Pawtucket from late 1916 onwards, where Henry opened the Canton Restaurant at 224 Main Street.

Goon’s business seems to have been successful, and he was a prominent figure in the local Chinese-American community. A 1920 newspaper article records him as president of the local branch of the ‘Chinese Nationalist League’ – the Guomindang.[1] The Pawtucket branch had been raising funds to support China’s economic development through the building of machine tool plants in Guangzhou. This was Sun Yat-sen’s political powerbase, and ‘it seems the Honolulu doctor’ – Sun – ‘suits [Goon’s] taste and that of the league’. Goon would later say that as a student he had heard Sun speak in Boston, and he and his wife had contributed to Sun’s fundraising drives at the time of the 1911 revolution.

Lully first found her photograph in the local press in June 1927, as ‘the first Chinese girl to graduate from Pawtucket High School’[2] She had been a bookish student, according to her high school yearbook profile:

There’s no hint of Lully the pilot here, unless you except the Latin tag: ‘Through Adversity to the Stars’ is the motto of Britain’s Royal Air Force. The profiles make it clear that it was Henry Goon who was the enthusiast. Fourteen years earlier he had flown with one of the Wright brothers at Marblehead; in 1927 he had watched Charles Lindbergh fly at Pawtucket. Earlier in 1928 a British pilot, Leonard Robert Curtis, had established a flight training school in the town, and now there was an opportunity for Henry to learn to fly, at least vicariously. ‘Yes, I’ll fly’, shy Lully was reported as saying.

The story broke in the Pawtucket Times on 14 June 1928: ‘Chinese girl here may teach nationalists how to fly planes’. And that day Curtis took Lully up: ‘Do you want me to do some tricks’, he asked, and then looped the loop, twice. This was the day the photographs were taken, for ‘camera and newspapermen’ were there to see her. ‘’I want to keep flying. I am not afraid. It was wonderful’, she said. ‘She is cool and she has the ambition. I’ll teach her’, said Curtis. It was the pilot’s show, of course. He had invited the newsmen, and fellow aviators presumably with the aim of securing publicity for his new business, gaining much, much, more than he might have hoped for.[3]

While most newspapers simply published this photograph, and a very brief caption, some carried a longer profile. Lully Goon, they said, was diffident but determined. She was quite camera shy, which suggests that her bemused self-possession as she stood on the biplane’s wing conveys something of the thrill of the day’s event. She had never been to China, she admitted, but was determined to help save it. She was her father’s daughter, it was implied. ‘I am a nationalist’, she said.

But rather than pilot training or training pilots, or going to China, or even to study literature at Brown, Lully Goon had already signed up for classes at the Department of Freehand Drawing and Painting at Rhode Island School of Design on graduating from high school, and kept on at her studies there until 1930. A portrait of her by Rhode Island artist Stephen Macomber is recorded as being exhibited at the sixth annual show of the Mystic Society of Arts in 1930, but of this side of her life I have found no other trace.[4] Curtis tried once more to make use of his star pupil (known to local readers, it seems, by her given name): ‘Lully may make parachute jump at coming meet’ ran an article in September 1928, reporting that she had written to the army to request a parachute. ‘I’m not afraid, … it will be a new thrill’.[5] Like the rest of her flying lessons that year (she was, it was reported, ill that summer), Lully’s jump did not take place.

Pawtucket Senior High School Yearbook 1927, p. 29 (via Ancestry.com)

She never flew, I think, and she certainly never got to China. In 1931 Lully married a New York University student, John Chung Sau Lee. Perhaps they had met at a meeting of the Chinese Students Alliance, in which she took part, speaking on behalf of the women delegates at the September 1928 meeting of its eastern chapter: Lully Veda Goon was her own woman. But around this point also she contracted pulmonary tuberculosis. The record goes quiet; the stars receded; adversity set in. In 1935 Lully Lee was a waitress at her father’s restaurant, but I can’t see her husband recorded there. On 2 November 1937 she died, after a long illness. She was still a pilot in the newspaper imagination: ‘Lully Goon Dies at Elm Street Home / Woman who hoped to train aviators for China succumbs’, ran a front-page item in the Pawtucket Times. Ironically, she died as ‘war planes roared over China’, and her husband was said to be serving in the Nationalist army.

Henry Goon ‘Restaurateur’ died in Plainville, Massachusetts, in December 1941, but he was also of course ‘the father of the … Chinese aviator who learned to fly … but died before she realized an ambition to train flyers for China in its conflict with Japan’. But Lully lives on in this image and as this image. The photograph can be found online, and – evidently – in vintage markets too. She is recorded in a history of women pilots in China. If she was not the first Chinese American to learn to fly, she was one of the earliest who started to learn to. What lingers with me is this inspiring and cheerful image of a young nationalist, a modern, enjoying her day in the skies: ‘It was wonderful.’

The Paris Times Sunday Pictorial Section, 26 August 1928, p. 2

I am grateful to Craig Clunas, for donating the photograph he found to the Historical Photographs of China platform — and of course for putting the question in the first place and inspiring this post — and to Douglas Doe, at the Rhode Island School of Design Archives for his assistance with Lully’s student records. The Rhode Island Historical Society’s website hosts the local newspapers that helped me dig out Lully Goon’s story and that of her family. Additional details came from searches in, amongst others, Newspapers.com, Gallica.bnf.fr, BritishNewspaperArchive.co.uk, Ancestry.com, and FamilySearch.

[1] Pawtucket Times, 22 September 1920, p. 4.

[2] Pawtucket Times, 30 April 1927, p. 1, 23 June 1927, p. 9.

[3] Pawtucket Times, 14 June 1928, p. 9, 15 June, p. 20.

[4] Hartford Courant, 3 August 1930, p. 7c.

[5] Pawtucket Times, 18 September 1928, p. 3.