Let’s remember, please: Wuhan is not an unknown place, it is not beyond our knowledge. Wuhan has long been a part, even of British lives — and many others overseas — intimately so, if unobtrusively. Produce from Wuhan fed British days. Tea was shipped out from the port and found its way eventually into British homes and down British throats (and Australian ones, and many others). Powdered and later liquid egg was sent out from processing plants in the city and would fetch up in British bakeries. A British day in the 1920s might this way be sustained by Wuhan produce. So this long relationship could not be more physically intimate. Wuhan’s direct entanglement with the world beyond Hubei province’s borders is nothing new. Caravans took tea overland to Russia. In 1868, SS Agamemnon, a British-owned steamer of the Blue Funnel line, sailed to the port to collect the first crop of new teas, ready to carry them swiftly direct to London. Wuhan was an internationally-connected city, even then, though mostly tea went first downriver to Shanghai for transhipment.

The city of Wuhan is actually formed of what were historically three cities: Wuchang, on the right bank of the Yangzi, opposite the mouth of the Han river that enters it from the north; Hanyang, on the opposite shore, west of the Han river mouth, and Hankou – written in the past as Hankow – to the east of the Han river. These cities have now grown together into the municipality of Wuhan. It has been a centre of revolutions, of a government in flight, and of international trade.

The city of Wuhan is actually formed of what were historically three cities: Wuchang, on the right bank of the Yangzi, opposite the mouth of the Han river that enters it from the north; Hanyang, on the opposite shore, west of the Han river mouth, and Hankou – written in the past as Hankow – to the east of the Han river. These cities have now grown together into the municipality of Wuhan. It has been a centre of revolutions, of a government in flight, and of international trade.

Foreign flags once flew there. After 1861 a slice of Hankou on the Yangzi riverbank was controlled by the British, and in time other neighbouring slices adjoining it by Russia, France, Germany, and Japan. In Hankow’s British Concession a British Municipal Council ran a police force, employed British nurses in its hospital and British teachers in its school, and oversaw a militia, the Hankow British Volunteer Corps. The Council laid down roads, collected property taxes, and documented its activities in a voluminous printed annual report. Hankow’s Britons sailed home to join up in the First World War, and those who died were commemorated on a now long-ago removed war memorial on the riverside bund, which was unveiled on Remembrance Day, 1922. To the northeast of the city a fine race-track was laid out, and foreign residents and Chinese alike flowed along the road on race days to join the festivities, watch the races, and of course to gamble. The track and surrounds ‘might well be in the heart of surrey’ remarked a visitor in 1938. Britons were born in Hankow, were married there or found partners there, and were interred there in the foreign cemetery. The city’s locally-printed English newspapers published notices of these life events. The descendants of Hankow unions live across the world. They might be your neighbours.

Foreign flags once flew there. After 1861 a slice of Hankou on the Yangzi riverbank was controlled by the British, and in time other neighbouring slices adjoining it by Russia, France, Germany, and Japan. In Hankow’s British Concession a British Municipal Council ran a police force, employed British nurses in its hospital and British teachers in its school, and oversaw a militia, the Hankow British Volunteer Corps. The Council laid down roads, collected property taxes, and documented its activities in a voluminous printed annual report. Hankow’s Britons sailed home to join up in the First World War, and those who died were commemorated on a now long-ago removed war memorial on the riverside bund, which was unveiled on Remembrance Day, 1922. To the northeast of the city a fine race-track was laid out, and foreign residents and Chinese alike flowed along the road on race days to join the festivities, watch the races, and of course to gamble. The track and surrounds ‘might well be in the heart of surrey’ remarked a visitor in 1938. Britons were born in Hankow, were married there or found partners there, and were interred there in the foreign cemetery. The city’s locally-printed English newspapers published notices of these life events. The descendants of Hankow unions live across the world. They might be your neighbours.

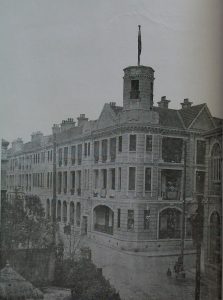

British Municipal Council building, Hankow Concession, flying the Union Jack

This was no innocent presence; it was one local manifestation of the wider British enterprise in China that had degraded the country’s sovereignty, and seen parts of other cities surrendered to British – and to Japanese, Russian, German, Italian, French, and other – concessions and settlements. The British had acquired a colony in Hong Kong in 1842, the Japanese took Taiwan in 1895, the Germans Qingdao in 1897. Tsarist Russia had seized great swathes of Siberia from China’s Manchu rules, the Qing. All of this in turn was of course part of the ravaging of the world by the great hegemons, the European empires, the United States, Japan. These gains were defended with violence. Those British Volunteers and British marines fired on and killed demonstrators in the city in 1925. Names familiar today had a presence there: the Hongkong & Shanghai Bank (now HSBC), ICI, British American Tobacco. The airline Cathay Pacific flies there twice daily today from Hong Kong. Into the 1930s its owners, John Swire & Sons, operated passenger and cargo services to the port from Shanghai through their China Navigation Company steamers.

Butterfield & Swire headquarters, Hankow, and Customs House under construction, 1923-24. Source: Historical Photographs of China, Sw-06-002 © John Swire & Sons, Ltd 2007.

Wuhan was a city at the centre of China’s great political resurgence in the twentieth century. It has been on the front pages of newspapers overseas more than once before 2020. In October 1911 revolutionary bomb makers accidentally blew themselves up there, prompting their comrades to launch the great military uprising that would lead to the toppling of the Qing dynasty. The republic that was then inaugurated floundered and in 1926 a new revolutionary alliance of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist party (the Guomindang), and the Chinese Communist Party, launched an audacious campaign to re-establish and reinvent the republic. The movement’s left wing head-quartered itself in Wuhan, establishing a revolutionary capital there. Wuhan’s people reoccupied the British concession, reclaiming it for their city: it never returned to British control despite the fury and tub-thumping of British politicians and British China hands downriver, and despite the fact that the left-wing was turned on by Chiang Kai-shek from his capital in Nanjing, and destroyed. Wuhan returned to the front pages in 1938 as the temporary capital of Chiang’s republic, which had withdrawn from Nanjing in the face of the Japanese invasion. ‘Defend Wuhan’ urges the poster below, but Wuhan fell to the Japanese in October 1938.

Wuhan’s history then is a history that was intertwined with wider global developments, international trade, imperialism, the rise of anti-colonial nationalism, the fascist onslaught of the 1930s, and slowly evolving resistance to it, first in Spain and then in China. In March 1938 the British poet W.H. Auden accompanied by the novelist Christopher Isherwood visited the refugee capital. ‘We would rather be in Hankow at this moment than anywhere else on earth’, wrote Isherwood. ‘History, grown weary of Shanghai, bored with Barcelona, has fixed her capricious interest upon Hankow’. Caprice again brings Wuhan to the world’s attention.

Poster: ‘Defend Wuhan!’. made by the ‘Korean Youth Wartime Service Corps’ (朝鲜青年战时服务团), founded in Wuhan in December 1937 by leftist Korean nationalists. Source: Historical Photographs of China, bi-s168.

For more on the city’s history see:

Chris Courtney, The Nature of Disaster in China: The 1931 Yangzi River Flood (Cambridge University Press, 2018)

William Rowe, Hankow: Commerce and Society in a Chinese City, 1796-1889 (Stanford University Press, 1984)

William Rowe, Hankow: Conflict and Community in a Chinese City, 1796-1895 (Stanford University Press, 1989)

My books The Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the QIng Empire, 1832-1918 (Penguin) and Out of China: How the Chinese Ended the Era of Foreign Domination (Penguin) chart the rise, fall and legacies of this historic degradation of China’s sovereignty, and the nature of the foreign-run establishment in Wuhan and other cities.