Actually, it came to almost 54 years: Thomas Carr Ramsey was unusual as a Briton in spending over half a century in China without leaving the country once. Of course, many Roman Catholic missionaries never left, but most foreign residents in China spent leave periods outside the country. Some worked for firms or oganisations such as missionary societies which had paid-leave policies, allowing them a furlough every five to seven years. This was deemed to be good for their health, but also for their general well-being, allowing them to reconnect with families. It did not suit everybody, and some found themselves at a loose end, distance and time having eroded their ties to their former homes. And of course, others were in China precisely to escape them.

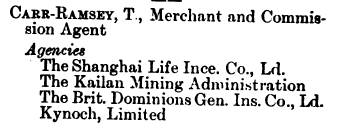

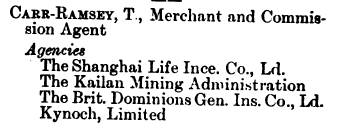

Directory and Chronicle 1917, Swatow

Many memoirs share the title (or variations on the theme): My Twenty-Five Years in China, or Forty Years in China, and so on — the latter, by consul Sir Meyrick Hewlett, is quite one of the battiest of the genre — but it was unusual for a man actually to be able to boast five decades unbroken residence in the country. The occasion it was marked, at Shantou (Swatow) with a reception at the foreigners’ Kialat Club, presentation of a bowl and ‘numerous scrolls and plaques, testifying in classical Chinese characters to his many virtues’, a Chinese banquet, a cinema show, and a performance by a Chinese military band. Ramsey responded with a rendition of ‘Auld Lang Syne’, though he was no Scotsman, having been born in South Shields, the son of Captain Henry Ramsey, who worked as a pilot in Swatow from 1876 until his death in 1883. So the family connection with this, one of the quieter and lesser-known treaty ports, was longer still.

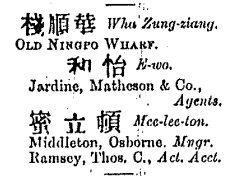

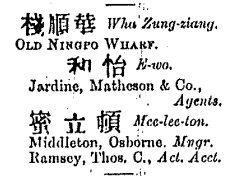

Directory & Chronicle 1905, Weihaiwei

The younger Ramsey arrived in China aged 15 on 24 September 1874, sailing out via Cape Horn and San Francisco on a vessel captained by an uncle. His career thereafter in China was peripatetic, but after 1909 he was based in Shantou. He first worked in a shipping office in Hong Kong, moved to Swatow, then on Shanghai, where he married in 1885, then moved on to Chefoo (Yantai) — where his father had previously lived — to a gold-mining venture. That failed, and he followed the flow of the expansion of the British presence in China by arriving in Weihaiwei shortly before it was formally handed over to the British, being present at the ceremony itself. After an altercation in the British court there over the probity of the firm he had established, and its practices in supplying the government (he was acquitted), Ramsey removed back to Swatow, where he secured the local agency for the British-owned Kailan Mining Administration, and became a stalwart in the Kialat Club, and in yachting locally (he designed his own boats). He also secured for a decade the position of Norwegian Acting Vice Consul, which must have been useful for something. On the way he surfaces frequently in the treaty port press as a sportsman: a champion jockey and a useful boxer.

Desk Hong List, 1884, Shanghai and Northern Ports, Shanghai section

It is the pattern of movement that interests me most, as well as, conversely, his fixity at Shantou and that of his family. When he died in Shantou in December 1931, Thomas Carr Ramsey was buried in a grave next to his mother in the now-lost Kakchieh Foreign Cemetery, while his son, Noel Ronald Ramsey carried on the firm’s business in the port after his death. Thomas Ramsey roamed along the China coast seeking opportunity but settled on exploiting a niche. You can find many like him in the archive, often moving swiftly, pouncing on new opportunities that opened as the political geography of China changed. The opening of a new treaty port, or leased territory, or a change in the rules that allowed foreigners to enter a new sphere of activity – mining, for example, or manufacturing – saw men leap in to try to secure a windfall profit (scooping up land at the first auction of lots was generally a sure-fire way to secure a good return), or otherwise exploit the advantage of early arrival. In the wider history of the treaty ports we know more about the successful than the not so lucky, but the latter always outnumbered the former. (The spectacular bankruptcy of Dent & Co. in 1865, sometime biggest rivals to Jardine, Matheson and Co, means that they are largely absent from histories of the China coast). Legal records are full of details of debts, bankruptcies, and the sorting out of estates. Sometimes, however, a man stands out in the record, and in this case one chanced into my line of sight, when I was looking for something else, through a little sub-heading in the North China Herald: ‘Mr. Carr Ramsey’s Jubilee’.

The man seems finally to have cracked: for on 13 June 1928 the ‘Norwegian Consul and Merchant’ (as he styled himself to the immigration authorities) landed with his wife in San Francisco on the SS President Grant, where he featured in the local press due to his ‘record’ stay in China, before making his way onwards to Britain. Sixteen months later he arrived in New York heading westwards; Ramsey’s wife, Ella Mary McLeod, followed him, dying in Swatow in 1935. This family was more widely embedded in the China coast world: his wonderfully named brother, Alfred Formosa Ramsey, was a ship’s engineer, who married the eldest daughter of the Inspector of Hong Kong’s naval dockyard police in 1893. One sister married a mariner in Chefoo in 1873, a man who was later Parks overseer at Shanghai for six years before his death in 1902, and whose family were a local fixture. Another sister married the founder of Shanghai’s Inshallah Dairy, A.M.A. Evans, who kept a fine herd of Jersey cattle in the east of the settlement. Thomas Carr Ramsey’s son Noel married the sister of a Chinese Maritime Customs officer, but his daughter Violet broke the China mould, and relocated to the Straits Settlements.

Swatow, a short hop by steamer from Hong Kong, was never a very successful treaty port, at least as judged in foreign minds, but it was an important point of movement of China to and from Southeast Asia, and prospered as a result of remittances from its diaspora. The city was comprehensively wrecked by a devastating typhoon in 1922, and was badly affected by the communist insurgency in eastern Guangdong province in the mid-late 1920s: in 1927 it was even briefly seized and held by Communist forces. Like many other ports it had its small foreign community, and contrary to assumptions that foreigners came, ‘plundered’ — a term I found in use only last week in a talk given by a Fudan University graduate — and then quickly went, the Ramsey family’s multi-generational story was not uncommon, nor was the way in which they had secured a comfortable niche. Old Swatow is now mostly invisible in today’s Shantou, and the port and its ilk are generally overshadowed by the bright lights (and richer records) of Shanghai, but it was an important part of the infrastructure of the China coast, and the Ramsey family itself in all its branches is emblematic of this now obscured world.

Sources: North China Herald, various, especially 25 October 1924, 8 December 1931; US immigration records via Ancestry.

Over the last couple of years I have been working with colleagues to transfer some of the scattered sets of biographical information that I have developed during research projects over the last two decades onto a new platform. The site, China Families, is now live, and still growing. Through various projects I had built up substantial sets of biographical information about men who served in the Shanghai Municipal Police (when developing Empire Made Me), the Chinese Maritime Customs Service (Chinese and foreign staff), and the shipping line China Navigation Co (whilst writing China Bound). An interest in the history of cemeteries and memorialisation amongst treaty port communities in China left me with sets of historic cemetery lists. These have now been combined with lists of civilian internees, neutral European nationals in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, and British government probate records, into a single searchable database. There are at least 60,000 records available. In addition I have developed a list of all the digitised copies of residents’ and business directories that I could find online, and provided guides for looking for men and women who lived in Hong Kong, and in Shanghai.

Over the last couple of years I have been working with colleagues to transfer some of the scattered sets of biographical information that I have developed during research projects over the last two decades onto a new platform. The site, China Families, is now live, and still growing. Through various projects I had built up substantial sets of biographical information about men who served in the Shanghai Municipal Police (when developing Empire Made Me), the Chinese Maritime Customs Service (Chinese and foreign staff), and the shipping line China Navigation Co (whilst writing China Bound). An interest in the history of cemeteries and memorialisation amongst treaty port communities in China left me with sets of historic cemetery lists. These have now been combined with lists of civilian internees, neutral European nationals in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, and British government probate records, into a single searchable database. There are at least 60,000 records available. In addition I have developed a list of all the digitised copies of residents’ and business directories that I could find online, and provided guides for looking for men and women who lived in Hong Kong, and in Shanghai.