My work has often considered questions of memory and history making, and of forgetting. A correspondent’s query nudges me to return to my files about a small case study of this that I very briefly mentioned in my book The Scramble for China, but had notwritten up more fully: one of the Shanghai International Settlement’s more obscure historic memorials, an imposing granite cross that stood in the grounds of the British Consulate-General from 1867 onwards.

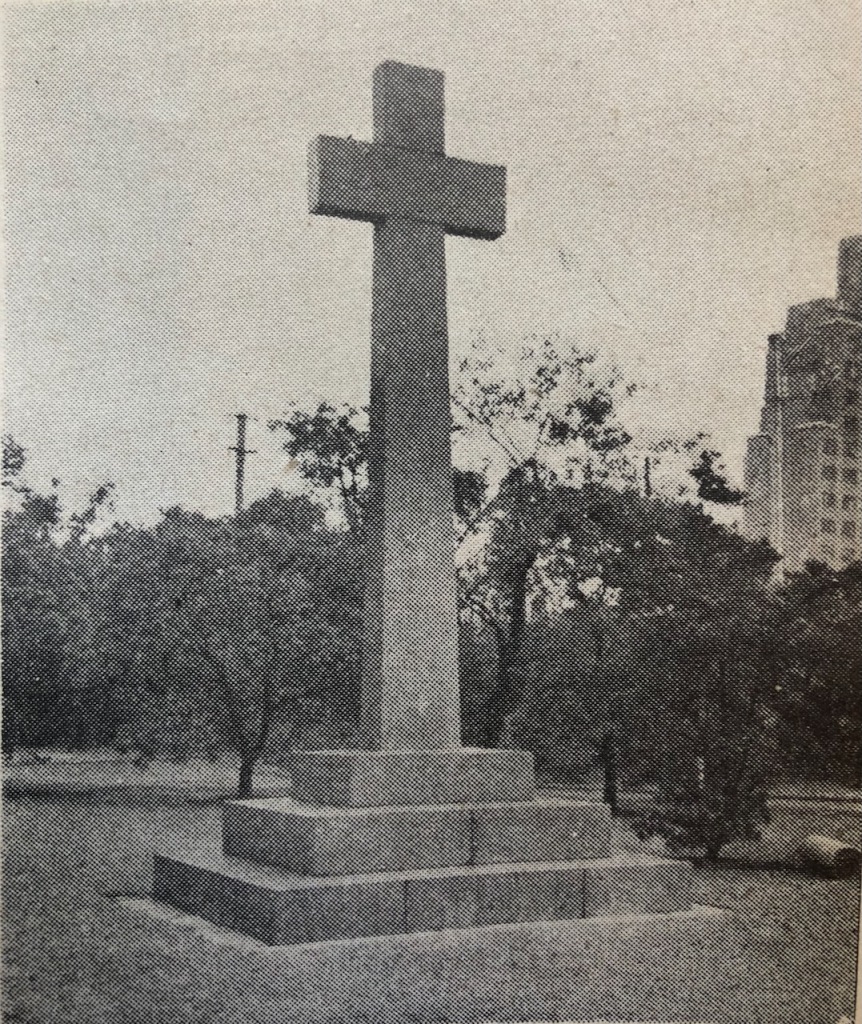

There is very little record of it, but its prominence can be gauged from the screenshot above from Pathé newsreel footage of the 24 May 1920 Empire Day parade in the Consulate-General grounds. Even so, correspondence from 1913 suggests British officials at the consulate had little understanding of its origins and in fact of what it commemorated, and even less faith that their successors would have any. Here it is almost two decades later, in a magazine article on cemeteries and monuments in Shanghai. (That’s Broadway Mansions, which faced along the Bund, that you can see to the right).

What none of these photographs convey is the fact that it was made of Peterhead granite: it was a deep red in colour, and as a result it was known in Chinese as the ‘Red Stone Memorial’, 红石纪念碑. As a magnified section of this much earlier photograph below shows, it did have some inscriptions around its pedestal, but aside from a religious text below, these were simply the names of five men. (This photograph, which seems to date from the late 1860s or 1870s, can be found here on the Chinese photographic history blog, Jiuyingzhi).

Two names can be made out in this image: Robert Burn Anderson, and (just) William De Norman, traces of another can just be made out. There were in fact five men listed here:

William De Normann

Born 28th August 1832, Died 5th October 1860

Robert Burn Anderson

Lieutenant and Adjutant Fanes Horse

Born 14th October 1833, Died 27th September 1860

Thomas Wilson Bowlby

Special correspondent of the Times newspaper

Born 7th January 1818, Died 25th September 1860

Luke Brabazon, Captain Royal Artillery

Supposed to have died

19th September 1860, aged 28

John Phipps, Private 1st Dragon Guards,

Born 1833, Died 18th September 1860

These were five of the men who died in captivity during the last stages of the Anglo-French invasion of north China during the Second Opium War. They were part of a group of nearly 40 taken when under flag of truce, some 14 of whom died from neglect or ill-treatment. Most of those who perished were Sikh troopers accompanying the group, which was travelling to parlay with Qing officials. No memorial was raised to them.

This episode, which prompted the invaders to seek to find a way to personally punish the Qing court, and resulted in the destruction of the Yuanmingyuan — the old Summer Palace — once held a central place in British memories of the conflict. However, noted Consul-General Sir Everard Fraser in the summer of 1913 in a letter to the British Minister in Peking, ‘the lapse of half a century has made their names and the incident commemorated quite unfamiliar to all but careful readers of Chinese history’. It would not have helped that the richly detailed first English-language Shanghai guidebook, Charles Darwent’s Shanghai: A Handbook for Travelers and Residents (1904) misread the most prominent of the names, and thereby misunderstood its meaning. As well as the ‘De Morgan’ Cross, it was various referred to, when mentioned at all, as the Bowbly Cross, or simply as a monumental cross.

The shaft of the cross did bear an inscription, but these echoes of Pilgrim’s Progress hardly helped tell its story:

Born in its light

Passing thro’ the dark valley

In its power

Resting in its shadow

Rejoice O Christian

In its great glory

Behold O Heathen

Enquire believe and live

Perhaps there should be something explicit, and less pious, pondered Fraser, and an additional inscription might be cut into the granite ‘briefly recording the deplorable act which cost the lives of the five persons whose names are cut upon the monument for the information of of the many visitors whose notice is attracted by the memorial’. A draft was enclosed: ‘This monument provided by Lady De Norman commemorates the death under most cruel torture of some members of the party who under a flag of truce went with Sir Harry Parkes on a mission of peace to the Commanders of the Chinese forces near Ho-hsi-wu and were there taken prisoners on 18th September 1860’.

The Minister asked the Legation’s Chinese Secretary, Sidney Barton, for his thoughts. Barton thought it best to leave it as it was. ‘The public having refused the custody of the monument, why cater for them now’, he wrote. Diplomatic and consular staff will know what it is, and wouldn’t the Chinese have a comment to make if such an inscription was added, especially with that reference to ‘cruel torture’. The time for such a brazen statement of anger was perhaps past; it would be best to leave it as it was.

Barton was alluding to the circumstances of the arrival of the monument in China. It had been conveyed to Shanghai in 1862, commissioned and sent out by William De Normann’s mother, and it was intended to form the centrepiece of the memorial at Beijing in the Russian cemetery where the remains of four of the five were interred in October 1860 (Brabazon’s body was never found). De Normann — who was christened Wilhelm Mererie Carl Helmuth Theodore von Normann — was the only son of his widowed mother, and had been born after his father’s death. These circumstances quite amplified her grief. But if there was a fullness of emotion, there were no funds to ship the monument north, and instead the ‘unwieldy packing cases’ were left to weather in the consulate grounds, providing a ‘favourite seat’, complained one newspaper correspondent in February 1867, for ‘seamen and other loungers at the British consulate’. Work on the new Public Garden, built on reclaimed land on the riverbank across the road from the consulate, was nearing completion. Might the Municipal Council like to offer it a home there, asked consul Winchester. No, reported the council, ‘there is a strong public feeling’ against this. After all, it was to be a park, not a graveyard. So a call to tender was published for the erection of the cross in the grounds of the consulate.

And there it stood, and probably did so until after the complex, abandoned in May 1967 after a week of intense Red Guard demonstrations, was forcibly requisitioned by the Shanghai city authorities in September 1967. Religious symbols of all kinds fell from the Shanghai skyline during the Cultural Revolution, and it is hard to believe that Baroness De Normann’s blood-red memorial to her son long lingered in the consulate grounds after they were taken over. But the Baroness’s grief and anger do in fact survive in stone in Northamptonshire, where a well-kept tombstone still lies for him, recording that ‘His mortal remains / Rest in the British cemetery / at Pekin / Having by the permission of God / Perished in captivity / In the cruel power of the heathen / After a captivity of sixteen days’. So a De Normann memorial, despite an erasure in Shanghai, still today tells one story of the China war of 1860 in a rural English churchyard. The ruins of the Yuanmingyuan, of course, tell another.

Sources: The National Archives, Kew, FO 228 1875, Shanghai No. 77, 5 June 1913, enclosures and minute; North China Herald, 16 February 1867, p. 27, 19 July 1867, p. 154; ‘Shanghai’s Cemeteries and Memorials’, Oriental Affairs IX:6 (June 1938), pp. 313-316; The London and China Telegraph, 14 October 1867, p. 539; The Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the Qing Empire, 1832-1914 (Penguin).

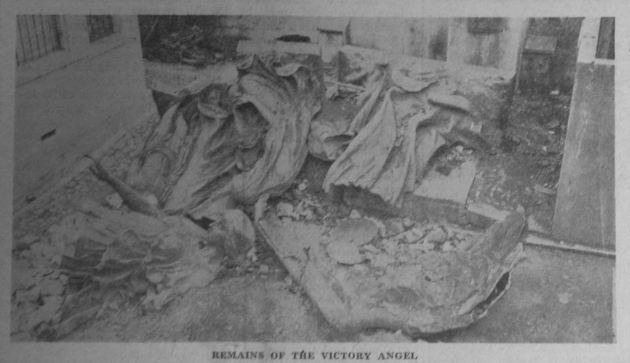

The Kaiser approved. Well, at least, his favourite sculptor Rheinhold Begas did, the man whose florid creations littered the sites of Wilhelmine power in Germany, and had oversight of the creation of the first German memorial erected in Shanghai. The Iltis Monument — the Iltis Denkmal, 伊尔底司碑 — commemorated the 77 dead German naval personnel, whose ship, the gunboat SMS Iltis, had foundered off the Shandong coast in July 1896. As the vessel sank the men were reported to have gathered around the mast and sung a hymn: ‘Now thank we all our God’. Three days earlier the ship’s officers had entertained Shanghai society at a reception on board, and so it seemed only proper that the International Settlement should host a memorial. The German seizure of Jiaozhou Bay (‘Kiaochow’), and the development of what became the city of Qingdao did not take place until 1897, and Shanghai hosted the largest community of the ‘China Germans’, who were inscribed as such — Die Deutschen Chinas — on the memorial itself.

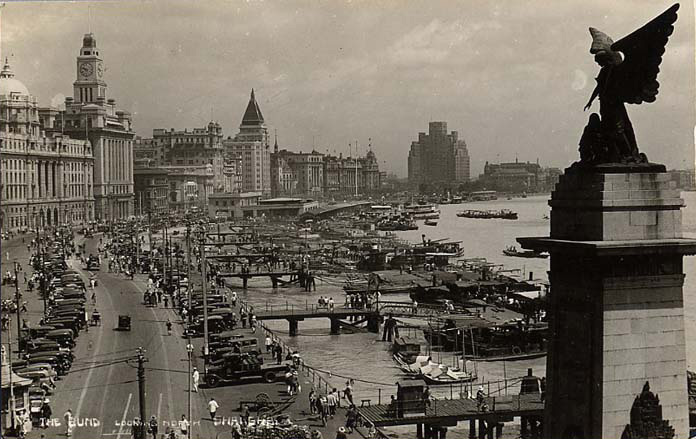

The Kaiser approved. Well, at least, his favourite sculptor Rheinhold Begas did, the man whose florid creations littered the sites of Wilhelmine power in Germany, and had oversight of the creation of the first German memorial erected in Shanghai. The Iltis Monument — the Iltis Denkmal, 伊尔底司碑 — commemorated the 77 dead German naval personnel, whose ship, the gunboat SMS Iltis, had foundered off the Shandong coast in July 1896. As the vessel sank the men were reported to have gathered around the mast and sung a hymn: ‘Now thank we all our God’. Three days earlier the ship’s officers had entertained Shanghai society at a reception on board, and so it seemed only proper that the International Settlement should host a memorial. The German seizure of Jiaozhou Bay (‘Kiaochow’), and the development of what became the city of Qingdao did not take place until 1897, and Shanghai hosted the largest community of the ‘China Germans’, who were inscribed as such — Die Deutschen Chinas — on the memorial itself. Three and a tons of bronze were cast into the shape of a broken mast, around which was wrapped a flag on a staff. A broken mast was a common funerary device, given added piquancy in this case by the facts of the Shandong disaster. The design was sketched by a German naval officer, and then the monument was designed by August Kraus. It was cast in Germany and shipped out to China where it was placed on the Bund, not far from the entrance to the Public Garden and close to the German Club Concordia.

Three and a tons of bronze were cast into the shape of a broken mast, around which was wrapped a flag on a staff. A broken mast was a common funerary device, given added piquancy in this case by the facts of the Shandong disaster. The design was sketched by a German naval officer, and then the monument was designed by August Kraus. It was cast in Germany and shipped out to China where it was placed on the Bund, not far from the entrance to the Public Garden and close to the German Club Concordia.

The statue shows Hart back bowed with the weight of his responsibilities, so it was hardly a subtle object, but unusually for the Bund memorials it also had a didactic text (see below). Hart, the words on panels attached to the plinth stated, was a ‘True Friend of the Chinese People’. He was ‘Modest, patient, sagacious and resolute’, it continued, ‘He overcame formidable obstacles, and / Accomplished a work of great beneficence for China and the world’. These are the words composed by Harvard’s Charles Eliot. Your ‘true friend of the Chinese people’, might well be my ‘black hand’ of British imperialism of course (to use a Chinese term), but the most controversial aspect of the memorial for some, at least until the Japanese takeover of the city in December 1941, was that the plinth was too small, and that the statue faced the wrong way. As those who Shanghai can see, it was positioned so that Sir Robert looked north, but this put it out of line with most of the other memorials on the Bund which were designed to be viewed with the river behind them, facing the buildings that lined the west side of the road.

The statue shows Hart back bowed with the weight of his responsibilities, so it was hardly a subtle object, but unusually for the Bund memorials it also had a didactic text (see below). Hart, the words on panels attached to the plinth stated, was a ‘True Friend of the Chinese People’. He was ‘Modest, patient, sagacious and resolute’, it continued, ‘He overcame formidable obstacles, and / Accomplished a work of great beneficence for China and the world’. These are the words composed by Harvard’s Charles Eliot. Your ‘true friend of the Chinese people’, might well be my ‘black hand’ of British imperialism of course (to use a Chinese term), but the most controversial aspect of the memorial for some, at least until the Japanese takeover of the city in December 1941, was that the plinth was too small, and that the statue faced the wrong way. As those who Shanghai can see, it was positioned so that Sir Robert looked north, but this put it out of line with most of the other memorials on the Bund which were designed to be viewed with the river behind them, facing the buildings that lined the west side of the road. In its new location the statue now faced west, and stood on a traffic island in front of the main entrance to the Shanghai Customs House, with its back to the Customs Examination shed. Presumably it then functioned to shame those sloping off early from work. Perhaps they snuck out the back of the building instead, in order to avoid his gaze. (But as the service also had photographs of Hart officially on display in offices, there was a limit to how far they could avoid the old ‘I. G.’). This was not the only one of the Bund side statues to move, in fact all did so, over the years. We might well be accustomed to thinking about the meanings of memorials shifting (or simply fading), but think less about the fact that the objects themselves, seemingly so rooted, are often shifted. Roads are widened or re-routed; anxieties lead to monuments being re-sited on private, instead of public land; political change demands a cleansing of a cityscape. Hart’s statue, along with all the others on the Bund, was taken down in September 1943, at the insistence of the Japanese authorities in the city.

In its new location the statue now faced west, and stood on a traffic island in front of the main entrance to the Shanghai Customs House, with its back to the Customs Examination shed. Presumably it then functioned to shame those sloping off early from work. Perhaps they snuck out the back of the building instead, in order to avoid his gaze. (But as the service also had photographs of Hart officially on display in offices, there was a limit to how far they could avoid the old ‘I. G.’). This was not the only one of the Bund side statues to move, in fact all did so, over the years. We might well be accustomed to thinking about the meanings of memorials shifting (or simply fading), but think less about the fact that the objects themselves, seemingly so rooted, are often shifted. Roads are widened or re-routed; anxieties lead to monuments being re-sited on private, instead of public land; political change demands a cleansing of a cityscape. Hart’s statue, along with all the others on the Bund, was taken down in September 1943, at the insistence of the Japanese authorities in the city.

Designed by Henry Fehr, who was responsible also for civic war memorials in

Designed by Henry Fehr, who was responsible also for civic war memorials in

![‘Qingzhu Zhonghua renmin gonghe guo chengli youxing (Shanghai)’ (Parade celebrating the Founding of the People’s Republic of China (Shanghai)’) [1950], Hangzhou National Art School, published by Mass Fine Art Publishing House](https://robertbickers.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/1950-bund-poster-pla.jpg?w=630)