A recent post on the blog Sikhs in Shanghai drew attention to a little known fact: Captain Edward Ivo Medhurst Barrett, C.I.E., Commissioner of the Shanghai Municipal Police, well known Hampshire cricketer, and the target for a bolt of lightning which struck Aldeburgh golf course in summer 1932, had also been a novelist. Barrett was fired for reasons that were never quite made clear in 1929, and was to die in 1950 when he was knocked off his bicycle. The novel, a secret agent thriller, Drums of Asia, was published by Lovat Dickson in 1934, the author being given as Charles Trevor.

A recent post on the blog Sikhs in Shanghai drew attention to a little known fact: Captain Edward Ivo Medhurst Barrett, C.I.E., Commissioner of the Shanghai Municipal Police, well known Hampshire cricketer, and the target for a bolt of lightning which struck Aldeburgh golf course in summer 1932, had also been a novelist. Barrett was fired for reasons that were never quite made clear in 1929, and was to die in 1950 when he was knocked off his bicycle. The novel, a secret agent thriller, Drums of Asia, was published by Lovat Dickson in 1934, the author being given as Charles Trevor.

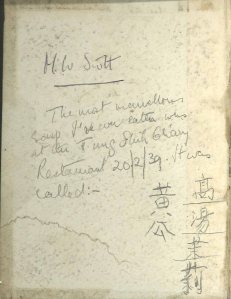

Barrrett had been recruited from the Malay States Guides to head the SMP’s Sikh Branch in 1907. Various records show him to be an important collaborator with Government of India intelligence activities in Shanghai aimed at countering Indian nationalist activities there. To find that he had written a novel which commences with German diplomats in Shanghai plotting to entice some Indian activists to organise a plot against the British in the pre-era was an enticing thought. ‘Herr Von Truebb-Blaich, German Consul-General in Shanghai was deep in thought’ it begins, as all such thrillers should. From the Consulate-General’s views of the Astor House Hotel and the ‘Whangpoo’ river, the plot ranges across the globe and fetches up with a finale in a barely disguised Afghanistan where it all unravels and the British Secret Service triumphs, predictably. What unexpected light, though, might it shed on Barrett’s role in Shanghai? How much was this a roman à clef? I had long wondered if Barrett was not in fact an intelligence agent of some sort, and perhaps this might shed light on that.

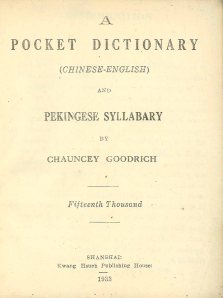

A file in the India Office Records noticed by Sikhs in Shanghai’s blogger promised some answers: entitled “Drums of Asia by Captain E I M Barrett alias Charlie Trevor: India Office correspondence with publishers on suggested changes prior to publication” (IOR/L/PJ/12/469, File 657/33), it details attempts by the India Office in London, liaising with MI5, and the Government of India, to thwart the book’s publication, or, as that was deemed impossible, to ‘shape’ the text. After all, one official notes, surely the India Office could not allow it to be alleged that British Secret Service agents operated under cover in foreign countries, could it? Well, another — perhaps more worldly colleague — remarked, it would not exactly be an entirely new fictional scenario. As you can see, Captain Barrett is identified as the author in the catalogue, and the file does have some interesting comments about him. He had, noted one man, ‘an ‘intimate knowledge of Indian political movements and individuals connected therewith’, and even though he was ‘very well known as a keen officer who did much for the Government of India in Shanghai’, he was also ‘impetuous and indiscreet’.

Alarms bells rang; the drums of Whitehall were beaten: memos were exchanged. New Delhi was contacted; MI5 was called on. A lengthy list was drawn up of troublesome passages and characterisations in the manuscript. Even though the nationalists who were named as plotters were now dead, officials worried that the characterisations would ‘give much offence in nationalist circles in India’. It could also prove difficult for relations with Afghanistan. In fact, publisher and author were actually to ‘behave in the most wonderfully accommodating manner’. The publisher, Lovat Dickson had brought the issue to the attention of officials himself, calling on them in early July 1933, pointing out that Barrett had supplied the facts, while the book had then been written up by a professional writer, by the name of Broadbridge. Much of the material was actually in the public domain, Dickson later argued, but he and Barrett proved more than happy to change plot details, names and locales, and generally defuse the book’s more worrisome factual elements.

Early memos and notes in the file show officials trying to work out who Barrett was, and how much he might really know. Someone clearly managed to find an old China hand who could oblige, and a month after the file was opened a note on Barrett was entered into the file, indicating also that he left the Shanghai police in those somewhat unclear circumstances and that he was now living in Aldeburgh. On 25 August, Dixon and Barrett called by arrangement on Sir Malcolm Seton, Deputy Under Secretary of State, to clarify how things stood. There must have been a perplexing phase in the discussion, for Barrett stated that he had never been in Shanghai in his life, and that his ‘only Eastern experience’ had been service with the West Kent Regiment on India’s North West frontier during the First World War.

Indeed it proved true: this was and has been a wild goose chase. India Office worries about security leaks and offending nationalist sentiment had been heightened by the belief that one of their own, with ‘intimate‘ knowledge of Government of India intelligence activities, was supplying the facts on which the ghost writer was preparing his text. Those of us interested in the colonial and anti-colonial politics of Shanghai had been bemused and pleased to find a prominent figure in that world writing what was presented as a lightly fictionalised account of events and personalities concerned. But the India Office cataloguers had finalised their summary of the file’s contents without getting to the bottom of its convoluted narrative. They had, we had, the wrong Barrett.

So we are left with Barrett the cricketer (that’s him, 3rd from left in this photograph on Sikhs in Shanghai) , rugby player, Sikh branch commander and police chief, and golfer, but not Captain Barrett, C.I.E., the novelist. However, we are also left with a previously unnoticed 1930s thriller partly set in Shanghai, and an interesting account in the file of the engagement of the British intelligence establishment and popular culture. But never fear: all is not in fact lost — that is, for those of us looking for novels written by Shanghai’s police commanders. Captain Alan Maxwell Boisragon, who held the post of Captain Superintendent in 1901 to 1906 obliges instead: his book for boys, Jack Scarlett: Sandhurst Cadet, was published in 1915. Was the War Office warned, we wonder?